The memories of the past or the forgetfulness of the present?

An awareness of a forgotten cultural inheritance, or the blissful fecundity of a governmental apathy? I really don't know...

Far into the rural regions of the Birbhum district, the last traces of a once-powerful Buddhist cultural community of Bengal now await their final obliteration in the hands of antiquity smugglers. And if we are talking about a criminal negligence of an archaeological kind, this is it.

The location is a cluster of villages under the Nalhati police station, about 32 kms from the Jharkhand border, and a few kilometres north of the station Lohapur, midway between the Azimganj-Nalhati routes of the Eastern Railways. Once an important centre of Vajrayana Buddhism through the 5th-12th centuries, the villages of Bara, Nagra, Baneswar, Kumarshanda and Sahakar, lie neglected and forgotten with their ruins.

The sights witnessed first hand can be quite unnerving...

A 1500 year-old decimated Buddhist pillar, with delicate carvings on it, lies face downward beside a pond in Bara village, on which the village women wash their laundry.

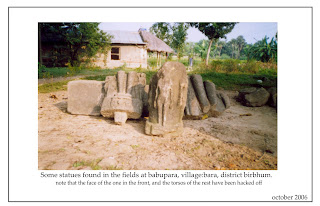

Horribly mutilated statues lie in the fields. Ploughshares regularly strike up statues and coins, none of which are ever reported. Fishing nets inadvertently tangle themselves in colossal stone pillars. And piled-up heaps of delicately-carved stone debris, possibly from ancient temples, vihars, or cities underneath, are carelessly strewn at crossroads to be picked up by the curious visitor or the apprentice-smuggler looking for a nice big opening in the international market.

If you aren’t plagued by conscience and need a paperweight with the face of a Yakshini which is more than a thousand years old, this is the place you go.

This cluster of villages in the northern fringe of Birbhum was an important centre for the Vajrayanis, and, if oral narratives are taken into account, once constituted the fabled city of

Mounds of ancient mossy bricks and black stone structures can be seen in superabundance, in a weatherproof confidence, still resistant to the vicissitudes of unregistered and undocumented human hate.

The surprising absence of stone quarries nearby suggests that the stones, mostly basaltic rocks, were apparently sourced from the Rajmahal Trap. Imagine them being transported by the forgotten master craftsmen of the tenth century, in heavily-laden boats down the Brahmani River and the Gambhira River, which now trickles as a dried-up stream 2 kms up north, delineating the district’s present border with Murshidabad.

Of the many broken statuettes of female figures that are worshipped by villagers as Hindu household deities (or secretly stored in the attics for future sales to the cross-border buyers arriving at Rampurhat or Suri), most are characterized by what the untrained eye finds similar to the

There are a few broken statues presumably made of Vindhyan sandstone here ―once sharply delineated shapes that have lost their chiaroscuro, attuned to a sense of loss deep down. Their obscure senescence can only be observed on the surface, for, till date, of stranger reasons, no archaeological excavations have taken place.

(Click on the image for a larger view)

A quick glimpse at the serried history footnotes then, all those to be mentioned in a flurry of generalities...

Under the Buddhist Pala kings of Bihar and Bengal (8th–12th century AD), Tantric Buddhism or Vajrayana had become the dominant religion here. The 7th-century travelling monk from

An individual’s enlightenment, they believed, arose from the realization that seemingly opposite principles are in truth one. This fundamental polarity and its resolution were often expressed through symbols of sexuality. Perhaps this explains the innumerous finds of coterminous male-female figures in these Birbhum villages, along with the intricately carved iconographic remnants.

Accused of incontinence by the Brahmins, the Vajrayanis worshipped deities like Yasodhara (the Buddha’s wife), the wives of the Bodhisattvas, and the Taras, and created a galaxy of gods and goddesses, even greater in number and diversity than the Hindu pantheon.

Later, they absorbed the mystic rites of Shaivite phallicism, and venerated the forms of Shiva-Kali and Radha-Krishna. As a cult, they flourished for more than seven hundred years in the regions from

An important feature of all tantras, as of the Vajrayanis, was the use of a polarity symbolism. On the physical level, it appeared as the union of male and female. On the ethical level, it appeared as the union of beneficial activity and an appreciation of what there is as it is. And on the philosophical level it appeared as the synthesis of absolute reality and absolute compassion.

Along with the Sahajyani Buddhist cult, the Vajrayanis were the ethnological precursors of the social basis which shaped the plebeian Sahajiya cult of the Vaishnavites, and the Bauls, for whom compassion for a suffering humanity still is a way to spiritual growth.

At present, there are no Buddhists living in the district. Perceivable, for the Indian chapter had ended nine centuries back. And none of the material artefacts available today for sighting are intact― further miracles have happened, and economic ones with no attention to historical flashbacks or educational animated cartoons.

Even after the Muslim conquests of the twelfth century, material traces of this powerful Buddhist culture survived. Near to the Pir Makhdum Hussein shrine, revered irrespective of religious beliefs in the region, the sacred antimension (the cloth upon which the divine liturgy of the saint is celebrated), shrouds one of the first Arabic stone inscriptions of

But a century of uninterrupted modern huckstering has taken its toll. The faces of all the larger-than-life statues found from the fields, have been mercilessly hacked away and pillaged. Only the torsos remain. Of the numerous statuettes discovered and lost, only one, of the Buddhist goddess Vajratara, has found its way to the Ashutosh museum, Kolkata. And for the 300 intact statues that were found in the course of the previous century, no records remain.

A brilliant metal statue of Marichi Devi, the Buddhist sun goddess, had been stolen a few years back. Villagers allege that the police had been in compliance. After the ensuing hullabaloo had subsided, the last of the recognized idols, of the Buddhist goddess Pragyaparamita, worshipped by the villagers as Bhuvaneswari, was stolen last year from her temple at Bazarpara.

“What can we individuals do?” said a Mr. Gorachand Dutta, who heads the village library at Bara, a lone crusader against the rampant antiquity smuggling of the region.

The library running in the village for 50 years,is in the memory of the same Gorachand!

“For three decades in vain, I had continually pleaded with the Archaeological Survey to step in," said Gorachand to the person who's posting this entry.

Each year, a number of these relics are further lost, smuggled. “Please don’t mention this in the papers,” said a villager, “You will excite further thefts.”

When asked of the district administration’s role in the preservation of these ruins, Mr. Gautam Gangopadhay, the District Information and Culture Officer, Birbhum, said with an eschatological mien, “We are yet to draw up a list of heritage sites in the district”, and added: "We could fill up the Bay of Bengal, if we had to dig around every supposed archaelogical site in this district."

Supposed? In 1916, the derelict Buddhist ruins at Bara and its adjoining villages had been specifically mentioned by the travelling Bengali scholar Harekrishna Mukhopadhay who, on personal initiative, had toured each of the district’s villages on foot. The results were the three encyclopedic volumes of Birbhum Bibarani (1916-1927) ― still regarded as the most extensive socio-archaeological study of the Birbhum district― on which many subsequent researchers have based their findings.

No traces remain of the statues that were meticulously listed by Mukhopadhay and preserved at the Hetampur Rajbari, the mansion of his funders. And sadly enough, the snapshots of the precious shapes captured in a box-camera, by Sri Bhoumick, the audibly-challenged photographer who accompanied Mukhopadhay across the district, remain the only tangible proof of their existence today.

(Draft of an article I submitted for publication to a newspaper in October 2006. After they refused publication, this went into select private circulation among friends. Two things happened in the meantime. I lost contact with a friend who had taken me there, after a 9-hour dusty journey on a motorbike without proper brakes and lights. And I failed to do a follow-up investigation. Things are, I presume, in the worse. But if someone is interested, I can provide you with a road-map. Just ask me...)

Click on each image for a larger view

4 comments:

Your article on the disappearing Buddhist relics was very disturbing, but, of course, I was glad to read it. One day, the ruins of the ruins won't be there at all anymore except for the occasional piece found in a private collection or as you said, being used as someone's paperweight. Thankyou for your good work. Judy Simon

www.buddhistinspiration.blogspot.com

Very good artical. Thanks for your information on this place and buddhism in past.

It is very Sad People just don't understand, preserve historical sites.

Instead of preserving these sites peoples are distroying and smuggling them. So sad!

Bharat @ TIBET ARTS

@ Judy Simons & Bharat:

I believe that this is a deliberate lapse in memory by people who're too engrossed in their present.

But thank you for your comments.

I am glad that you voiced out about this. Although some people would put little emphasis on the past, many would prefer such relics to reach a museum and/or be given proper respect.

Post a Comment