the leery light of childhood,glimpses into a dizzying world of fearful and pointless gestures, and other listless adventures...

After a day of intense neurotic reading

You realise your being, and ah, also that mutual recognition of responsibility that only happens on a plane of mutuality. Imagined, i.e. deep inside your mind, a simulacrum invented by neurons, a neurotic activity, anyway.

Creation is thought, desired, projected and organized. Your mind silently works on destruction. And destruction is a creative joy.

So sayeth the ancients.

Remembering to forget

If the construction of memory is a core theoretical issue in historical and cultural analyses, understanding how personal memories give way to forgetfulness and selective attention is a damn confusing area.

"We'll remember," we swear, but we happen to forget. Why is that? Just because our brain cells get renewed after certain periods of time, and we emerge as newer forgetful humans after that? I don't think the answer is that simple. But it's the question that worries me further. What accounts for my selective remembering and unremembering?

And then, and without recourse to the Jungian collective subconscious, which is of course extremely stupid, my memory is never about the past alone and, at least in its guise as commemoration, never private and solely individualised. There are contestations, skirmishes, memorials and commemorations about the present as well as about the past, and since commemoration tends to make past and present as stiff and as a freely-flowing linear continuity, competing moral-aesthetic orders of the present make up my choices of refering back. "He who controls the present, controls the past. He who controls the past, controls the future," as Orwell put it in another context. But let me reframe the question once again: Do we chose to remember? Do we chose to forget? Even when we've emphatically claimed to do otherwise?

On liquid recollections

Close to the rented house a diseased old mango tree stands shivering in the midnight rain. I had never seen it before, for there used to be a house in the middle, obstructing my view for over a year. A gaping hole on the ground, and some rain-drowned debris, marks the house's absence. But the leaves of the tree tremble in the dark, the relentless rain makes a strange pattern of awareness or memory.

Close to the rented house a diseased old mango tree stands shivering in the midnight rain. I had never seen it before, for there used to be a house in the middle, obstructing my view for over a year. A gaping hole on the ground, and some rain-drowned debris, marks the house's absence. But the leaves of the tree tremble in the dark, the relentless rain makes a strange pattern of awareness or memory.Black, turbid, liquid memories of the multiple pasts and presents suddenly oozes out of nowhere, and like busy and confused insects lost in the rain, agonise your minds. It is in these intense moments you get to feel that the tree's silent presence, the tranquilising nocturnal of rain falling, and your vacuous stare into a blinking screen, are the only sure proof of your existence and of the reflected reality of the world, outside this strange city cage of concrete and glass. Makes you realize that memory is forever liquid, but never lost to time, for it makes a pattern of timeless moments.

Drawing the perfect crab

The king asked Chuang-tzu, an expert draftsman, to draw a crab.

Chuang-tzu replied that he needed five years, a country house, and twelve servants.

Five years later the drawing was still not begun.

"I need another five years," said Chuang-tzu. The king granted them.

At the end of these ten years, Chuang-tzu took up his brush and, in an instant, with a single stroke, he drew a crab, the most perfect crab ever seen.

[Source: Calvino's Memos for the New Millenium; Picture by Ch'i Pai-shih (1863-1957)]

Kari and the River of Memories

Though the marshes, ponds and lagoon-lakes have vanished from the urban Indian cityscape, in deep cavernous spaces within the multiple minds of the archetypal Indian city, flows a strange river. The buildings seem to rise on it. But look closer, the silent river flows underneath. This silent river, that mystic river, is not Lethe, honey; and it’s not Mnemosyne either. This river feeds on memory; it plays with forgetfulness.

And this could have been anywhere, as the story goes, but this happens to be in ‘smog city’ Mumbai.

Often neglected in printspace, animals are ritually drowned in this river by archaic local cults, offerings of bags of plastic, faeces, refuse, unidentified corpses, electronic junk, friends and incomprehensive parents are offered to it, those which clog the arterial flow of this river; there are numerous tales of a traveller lost forever to time when she discovers the river in her lonely evening walks, or is carried by river spirits fascinated by her beauty.

Of the few strange people who’ve experienced the river’s stranger shores as essential to humans for survival, decline to speak of it; only someone with the innocence of an Orpheus, and with wounds impossible to heal, can summon up the courage to speak of it. But none dare to act boatman; the waters speak of unknown depths. And no one thinks of the traveller, one or many among the crowd, for the river just keeps rolling, along, with the share of individual and collective memories, washed away.

If the above appears garbled speech to you, better not read Amruta Patil’s Kari.

Yes, the graphic novel in India has finally come of age, even though the recognition is far from proper.

I had been waiting to read it, and after going through the reading, spent a month or two, after the initial hype was over, to summon up the courage to speak on it. Meanwhile, I have skimmed through blogs and other interesting places where they make reviews— I couldn’t find a proper reference to the river itself, which connects, rather interweaves the stories of Kari, Ruth, Angel, and others, into a complex narrative beyond metaphors.

In my reading, however, the river is central to the graphic novel; it is the silent protagonist, the boatman, the city, the memories of the city and other cities, and memories of memories. The characters’ lives are situated within and set by the river's boundaries, and like true magic, these lives weave solitude and melancholy into a beautiful completion which spreads out wings, contemplating a journey, better to say a return, to an impossibility where the strange river that feeds on memories empties itself in a desperate response to its slow painful drying, until the buildings and apartments sinks in it again at the end of the book, and in the surge of memories, the boatman becomes you.

If you haven't read Kari, you've really missed something...

I got proof

The certificate. The atavism of this confused pudding. The material of the muffled metaphor. I had cleared high school ten years back.

The baboo I had talked to on my earlier visit was absent, and it was strange to find, after the time spent on "requests, reminders and re-reminders" (if there is such a word), that the file containing the certificates was in a cupboard just next to his desk, fished out innocently by someone who went about pretending to be busy for the time I waited for a change in their insouciance.

I also found there're around 20 or more guys, my college-level classmates, who've not picked up their certificates. One of them, as far as I know, is in Delhi working in an advert firm, another is writing codes for a software firm of the US. Trouble lies in wait for them, in case they want to register for PhD. Hopefully, they won't.

I felt angry in a way. The absent baboo could have given me the document the earlier day itself. Or it could have been had without the unnecessary wait. It's all about attention-demanding bureaucratic self-importance on part of people toying with whatever little power they have in their hands.

But share my elation! For now I've got solid proof: I had indeed cleared high school ten years back.

Picturing Gorkhaland: Via Darjeeling and the Bengali mind

I had been waiting for the pictures to appear. Pictures that would prevent me from saying overtly political things in this precious little space I had saved for myself.

But my photographic senses let me down; the negatives carried only the dark shades surrounding the images I had hoped to register. And strange green spots. Only a few pictures materialized from the darkroom. Bless you.

Or else, you could be seeing pictures of the serene mountain mists sliding down windy wet terraces, once again, pictures of balaclava-clad Bengalis in dhotis enjoying a three-day spell of pleasant winter chill and attempting horse-riding while summer was blazing on the plains, Prasant Tamang singing in a cracked voice to a crowd of youngsters, and the silent blazing eyes of women marching for an autonomous Gorkhaland through the streets of Sukhia Pokhri.

For my return from the Darjeeling Hills coincided with escalating violence in the region; violence that simmers right now, but violence, like all violence, that feeds on itself and waits for an opportune moment to spring in.

The newspapers published from Kolkata that I still happen to read each morning had shamelessly fed on the violence throughout the last month. “Tourists hounded off the hills”— had been the frenetic refrain. Nothing of the sort, except a few awkward glances of people encountered, isolated acts by those idiots who always think in terms like “we” and “they” and squabble, squat, spit, bicker and bite, creating trouble for others, burning buses, deliberately hurting “them”, always believing that their political leaders will make the world a better place for "we" to live in and give "us" identities, at least recognition of some sort, and finally, the alacrity of people who always find themselves on the receiving end.

“Believe in me, I’ll give you Gorkhaland,” goes a small poster bearing the picture of Bimal Gurung, that I saw stuck on many walls in Darjeeling. I found it strange that people are believing in Gurung after they had experienced Ghising. Many hill-people I talked to during my trip, made exclamations of this sort: “We’ve little of a choice. At least we know now he’s one of us, and trying hard.”

Repetition of a horizontal level of comradeship that has been absent, but one that has always imagined in similar nationalistic imaginings of antethetical nature. Or how would you explain an eight-year-old Bengali boy working for fifteen hours at a stretch in a Mall-side Darjeeling hotel owned by a Bengali, if they share a common bonding of some sort, let's say, er, hmm, a colonial past? But you find that it’s stranger that the desperation, that drives hill-people to believe in the GJMM’s capacity for change, is often ignored.

This desperation is not fired by a political imagination, true, but is also nurtured by a series of serious iniquities. As Mahendra P. Lama, the man who prepared the first Development Plan of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council in 1989, puts it in an article:

Today, the people of the Darjeeling district are demanding answers to questions such as why the entire tea and cinchona industry is in the doldrums, what happened to the rich forest resources, why are there starvation deaths in the Dooars tea gardens, why are the three hill subdivisions still crying for drinking water and basic health facilities, and why Darjeeling has only two drinking water reservoirs in Sinchal, built in 1910 and 1931 by the British administration. There are various other signs of neglect by the state government. There are no panchayats in Darjeeling and hardly any Central government schemes are implemented here. Except in the state assembly, the people of Darjeeling figure nowhere in the decision-and policy-making process of West Bengal... (Storm brewing in the Mountains)With or without considerations of Gorkhaland autonomy, or whether the GJMM is capable of redressal, these are the questions people living in West Bengal, and those on the seats of power, should also be asking.

The problem, I think, has another important dimension. Not to be found in Anjan Dutta's movies, though, even when it got something to do with the average Bengali's mindset.

There are some deep-seated sickening notions of a racial nature that are left untouched, especially by Bengalis, who form the dominating group in the region, and are simultaneously nostalgic, romanticizing and ignorant to the region from afar. Self-critical Bengalis have no problems with hill-people as long as they are loyal domestic helps and servants, lovingly called “Kancha” or “Bahadur”, irrespective of their proper names, and relegated to work relating to broadly-defined manual labour, or infantry-level military service. And note, how the pictures of retired Gorkha soldiers peacefully marching for autonomy and beaten up mercilessly by the West Bengal police, have conveniently receded from media memory. That communal Bengali organisations like Amra Bangali have found space in and around Siliguri, and support from the ruling parties, shows that the mindset of greater Bengali “racial superiority” has not changed much in years.

As long as this stupid segregration of peoples exist in the minds of the dominant group, the birds, flowers, clouds and hill-peoples, and also all the people living in the plains, I fear, have further trouble waiting for them. I can only share an apprehension. And meanwhile, no worthwhile images to be displayed that have survived my trip.

Find Dangerous Drugs Here: "Reiteration"

India has become a dumping ground for banned medicine; also the business of producing that is booming. Apart from spurious medicine sold from registered medicine shops, there are some dangerous drugs that have been globally discarded, but are freely available in India, with or without the doctor's prescriptions.

Never did I know that Enteroquinol, the one I used to pop in from time to time, caused damage to eyesight. Or Nise, that painkiller I preferred for I didn't have to use an antacid, causes trouble for your liver. You, too, might have surprises waiting for you.

Do check the list below to see if you have been using any of these.

And spread the word.

PHENYLPROPANOLAMINE:

cold and cough. Reason for ban : stroke.

Brand name : Vicks Action-500

ANALGIN:

This is a pain-killer. Reason for ban: Bone marrow depression.

Brand name: Novalgin

CISAPRIDE:

Acidity, constipation. Reason for ban : irregular heartbeat

Brand name : Ciza, Syspride

DROPERIDOL:

Anti-depressant. Reason for ban : Irregular heartbeat.

Brand name : Droperol

FURAZOLIDONE:

Antidiarrhoeal. Reason for ban : Cancer.

Brand name : Furoxone, Lomofen

NIMESULIDE:

Painkiller, fever. Reason for ban : Liver failure.

Brand name : Nise, Nimulid

NITROFURAZONE:

Antibacterial cream. Reason for ban : Cancer.

Brand name : Furacin

PHENOLPHTHALEIN:

Laxative. Reason for ban : Cancer.

Brand name : Agarol

OXYPHENBUTAZONE:

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Reason for ban : Bone marrow depression.

Brand name : Sioril

PIPERAZINE:

Anti-worms. Reason for ban : Nerve damage.

Brand name : Piperazine

QUINIODOCHLOR:

Anti-diarrhoeal. Reason for ban : Damage to sight.

Brand name: Enteroquinol

(from an email forwarded by a friend who's a public health activist)

Carry Away Relics

The memories of the past or the forgetfulness of the present?

An awareness of a forgotten cultural inheritance, or the blissful fecundity of a governmental apathy? I really don't know...

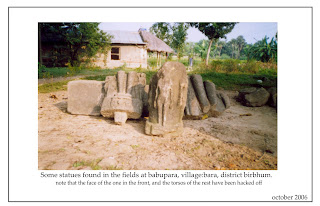

Far into the rural regions of the Birbhum district, the last traces of a once-powerful Buddhist cultural community of Bengal now await their final obliteration in the hands of antiquity smugglers. And if we are talking about a criminal negligence of an archaeological kind, this is it.

The location is a cluster of villages under the Nalhati police station, about 32 kms from the Jharkhand border, and a few kilometres north of the station Lohapur, midway between the Azimganj-Nalhati routes of the Eastern Railways. Once an important centre of Vajrayana Buddhism through the 5th-12th centuries, the villages of Bara, Nagra, Baneswar, Kumarshanda and Sahakar, lie neglected and forgotten with their ruins.

The sights witnessed first hand can be quite unnerving...

A 1500 year-old decimated Buddhist pillar, with delicate carvings on it, lies face downward beside a pond in Bara village, on which the village women wash their laundry.

Horribly mutilated statues lie in the fields. Ploughshares regularly strike up statues and coins, none of which are ever reported. Fishing nets inadvertently tangle themselves in colossal stone pillars. And piled-up heaps of delicately-carved stone debris, possibly from ancient temples, vihars, or cities underneath, are carelessly strewn at crossroads to be picked up by the curious visitor or the apprentice-smuggler looking for a nice big opening in the international market.

If you aren’t plagued by conscience and need a paperweight with the face of a Yakshini which is more than a thousand years old, this is the place you go.

This cluster of villages in the northern fringe of Birbhum was an important centre for the Vajrayanis, and, if oral narratives are taken into account, once constituted the fabled city of

Mounds of ancient mossy bricks and black stone structures can be seen in superabundance, in a weatherproof confidence, still resistant to the vicissitudes of unregistered and undocumented human hate.

The surprising absence of stone quarries nearby suggests that the stones, mostly basaltic rocks, were apparently sourced from the Rajmahal Trap. Imagine them being transported by the forgotten master craftsmen of the tenth century, in heavily-laden boats down the Brahmani River and the Gambhira River, which now trickles as a dried-up stream 2 kms up north, delineating the district’s present border with Murshidabad.

Of the many broken statuettes of female figures that are worshipped by villagers as Hindu household deities (or secretly stored in the attics for future sales to the cross-border buyers arriving at Rampurhat or Suri), most are characterized by what the untrained eye finds similar to the

There are a few broken statues presumably made of Vindhyan sandstone here ―once sharply delineated shapes that have lost their chiaroscuro, attuned to a sense of loss deep down. Their obscure senescence can only be observed on the surface, for, till date, of stranger reasons, no archaeological excavations have taken place.

(Click on the image for a larger view)

A quick glimpse at the serried history footnotes then, all those to be mentioned in a flurry of generalities...

Under the Buddhist Pala kings of Bihar and Bengal (8th–12th century AD), Tantric Buddhism or Vajrayana had become the dominant religion here. The 7th-century travelling monk from

An individual’s enlightenment, they believed, arose from the realization that seemingly opposite principles are in truth one. This fundamental polarity and its resolution were often expressed through symbols of sexuality. Perhaps this explains the innumerous finds of coterminous male-female figures in these Birbhum villages, along with the intricately carved iconographic remnants.

Accused of incontinence by the Brahmins, the Vajrayanis worshipped deities like Yasodhara (the Buddha’s wife), the wives of the Bodhisattvas, and the Taras, and created a galaxy of gods and goddesses, even greater in number and diversity than the Hindu pantheon.

Later, they absorbed the mystic rites of Shaivite phallicism, and venerated the forms of Shiva-Kali and Radha-Krishna. As a cult, they flourished for more than seven hundred years in the regions from

An important feature of all tantras, as of the Vajrayanis, was the use of a polarity symbolism. On the physical level, it appeared as the union of male and female. On the ethical level, it appeared as the union of beneficial activity and an appreciation of what there is as it is. And on the philosophical level it appeared as the synthesis of absolute reality and absolute compassion.

Along with the Sahajyani Buddhist cult, the Vajrayanis were the ethnological precursors of the social basis which shaped the plebeian Sahajiya cult of the Vaishnavites, and the Bauls, for whom compassion for a suffering humanity still is a way to spiritual growth.

At present, there are no Buddhists living in the district. Perceivable, for the Indian chapter had ended nine centuries back. And none of the material artefacts available today for sighting are intact― further miracles have happened, and economic ones with no attention to historical flashbacks or educational animated cartoons.

Even after the Muslim conquests of the twelfth century, material traces of this powerful Buddhist culture survived. Near to the Pir Makhdum Hussein shrine, revered irrespective of religious beliefs in the region, the sacred antimension (the cloth upon which the divine liturgy of the saint is celebrated), shrouds one of the first Arabic stone inscriptions of

But a century of uninterrupted modern huckstering has taken its toll. The faces of all the larger-than-life statues found from the fields, have been mercilessly hacked away and pillaged. Only the torsos remain. Of the numerous statuettes discovered and lost, only one, of the Buddhist goddess Vajratara, has found its way to the Ashutosh museum, Kolkata. And for the 300 intact statues that were found in the course of the previous century, no records remain.

A brilliant metal statue of Marichi Devi, the Buddhist sun goddess, had been stolen a few years back. Villagers allege that the police had been in compliance. After the ensuing hullabaloo had subsided, the last of the recognized idols, of the Buddhist goddess Pragyaparamita, worshipped by the villagers as Bhuvaneswari, was stolen last year from her temple at Bazarpara.

“What can we individuals do?” said a Mr. Gorachand Dutta, who heads the village library at Bara, a lone crusader against the rampant antiquity smuggling of the region.

The library running in the village for 50 years,is in the memory of the same Gorachand!

“For three decades in vain, I had continually pleaded with the Archaeological Survey to step in," said Gorachand to the person who's posting this entry.

Each year, a number of these relics are further lost, smuggled. “Please don’t mention this in the papers,” said a villager, “You will excite further thefts.”

When asked of the district administration’s role in the preservation of these ruins, Mr. Gautam Gangopadhay, the District Information and Culture Officer, Birbhum, said with an eschatological mien, “We are yet to draw up a list of heritage sites in the district”, and added: "We could fill up the Bay of Bengal, if we had to dig around every supposed archaelogical site in this district."

Supposed? In 1916, the derelict Buddhist ruins at Bara and its adjoining villages had been specifically mentioned by the travelling Bengali scholar Harekrishna Mukhopadhay who, on personal initiative, had toured each of the district’s villages on foot. The results were the three encyclopedic volumes of Birbhum Bibarani (1916-1927) ― still regarded as the most extensive socio-archaeological study of the Birbhum district― on which many subsequent researchers have based their findings.

No traces remain of the statues that were meticulously listed by Mukhopadhay and preserved at the Hetampur Rajbari, the mansion of his funders. And sadly enough, the snapshots of the precious shapes captured in a box-camera, by Sri Bhoumick, the audibly-challenged photographer who accompanied Mukhopadhay across the district, remain the only tangible proof of their existence today.

(Draft of an article I submitted for publication to a newspaper in October 2006. After they refused publication, this went into select private circulation among friends. Two things happened in the meantime. I lost contact with a friend who had taken me there, after a 9-hour dusty journey on a motorbike without proper brakes and lights. And I failed to do a follow-up investigation. Things are, I presume, in the worse. But if someone is interested, I can provide you with a road-map. Just ask me...)

Click on each image for a larger view

Tree-faced sanity

Societal culture had always created a slew of new poseurs with affectations and idiosyncrasies that sane people earlier found easy to ridicule.

Societal culture had always created a slew of new poseurs with affectations and idiosyncrasies that sane people earlier found easy to ridicule.True, in the crux of that ridicule lay ignorance, apathy, superstition, political blinkers or cultural incomprehensibility, and the hostility of a people who considered themselves hypothetically sane; sanity was, and is, always a confusing term. The constants that people used to assume, always melts away to incomprehension, or to newer constants.

But here, I am speaking in specific terms, like the sanity that goes into the planting of rice-buds in the rainy seasons, and not in the blight of summer, or something that teaches you to be observant, if not critical, when the world around is changing fast to far-fetidness. The sequence of the conceptions is at the same time a sequence of realisations, as the grand old man put it.

This brings us to what I would like to call tree-faced sanity. It is a category in preconception, self-relation and self-realization in a removed societal fabric, approximating as universal infinitude. It assumes a lot, and is itself subject to varicose interpretations. It's distinct from the above sane 'sanity', for it talks big structures and branches, and does precisely nothing to realize.

Does scorn and ridicule build up inside you, even when you choose to remain silent, hearing people talking tree-faced sanity? Is it discernible from your face? Careful then— the edges are showing.

But tell me: Do you consider yourself sane?

[Pix: Jurgen Habermas and a tree-face]